An exclusion zone put in place by Bay of Plenty Regional Council following an oil spill eventually paved the way for a landmark court ruling. This confirmed that regional councils have jurisdiction to control the taking of fish, provided this is not for a Fisheries Act 1996 purpose but for the purpose of maintaining Indigenous biodiversity or other resource management values.

In 2011, the MV Rena struck Ōtāiti (Astrolabe Reef) and spilt an estimated 350 tonnes of heavy fuel oil.[1] It was Aotearoa New Zealand’s worst oil spill by volume and many fish and more than 1,000 seabirds were directly impacted by the spill.

Following the spill, an exclusion zone was set up around the vessel so that salvaging operations could take place. The exclusion zone was established on the basis of navigational safety under the Maritime Transport Act 1994 and the Bay of Plenty Regional Council’s navigation safety bylaw.

The reefs near Motiti Island in the Bay of Plenty support significant marine biodiversity, landscape and cultural values. The Bay of Plenty has decades of monitoring data for coastal and estuarine ecosystems, which provided a scientific baseline against which to measure the impacts of the MV Rena. In this case, the combination of the coastline type, duration of spill, rapid response, and many other factors, meant that the Te Moana-a-Toitehuatahi Bay of Plenty coastal ecosystem showed significant resilience.[2]

A gem doris/nudibranch (Dendrodoris krusensternii) observed in the Motiti Natural Environment Management Area in 2020. Image credit: Lukas Phan-huy/iNaturalist (CC BY-NC 4.0).

The absence of fishing in the exclusion zone allowed much of the marine life to increase and demonstrated the significant natural biodiversity of this area.[3] Motiti Island is unique in having a resident population of predominantly tangata whenua. They have had a long intergenerational aspiration for the reservation of the rohe moana to preserve their wāhi taonga, wāhi tapu and other cultural and environmental significance preserved as a taonga moana for their hapū and the shared benefit for the wider community. In this endeavour, the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust was established (prior to the MV Rena grounding) to allow representation on behalf of tangata whenua of Te Moutere o Motiti in legal proceedings, primarily on behalf of Ngā Hapū o te Moutere o Motiti. However, it is important to note that there are diverse tangata whenua views and not all residents of Motiti feel they are represented by the Trust.

While the grounding was not the genesis of legal efforts, it provided a dataset that supported what tangata whenua had known for many generations – that there had been significant degradation of their rohe.

As described by the Chairman for the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust and kaumātua of Te Moutere o Motiti, Umuhuri Matehaere, “Nature began to restore itself. Potential for good came from the bad.”[4] The Trust considered that the reef continued to need “time to heal and rest so that it can re-emerge to its full health.”[4] However, the exclusion of fishing was on the basis of navigational safety and once this risk was minimised and the exclusion zone was removed, fishing activities would recommence as they previously had.

Nature began to restore itself. Potential for good came from the bad.”

The Trust made an application under the Fisheries Act 1996[5] for a temporary closure of the fishing area, which was not successful for a number of stated reasons, including the lack of wide consultation with tangata whenua. Legal action continued over several years, starting with an appeal to the Regional Coastal Environment Plan followed by the Environment Court, High Court and Court of Appeal. Levers for protection under the RMA 1991 regarding the functions of regional councils were explored.[6]

The court case highlighted conflict between the RMA 1991 and the Fisheries Act 1996 in how the marine environment is regulated. The purpose of the Fisheries Act 1996 is to provide for the utilisation of fisheries resources while ensuring sustainability. While the need to ensure sustainability has led to the introduction of measures regarding bycatch, benthic impacts, changes to biodiversity and protection of habitats, the implementation of available sustainability tools has been variable.[7]

The court case highlighted conflict between the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Fisheries Act 1996 in how the marine environment is regulated.

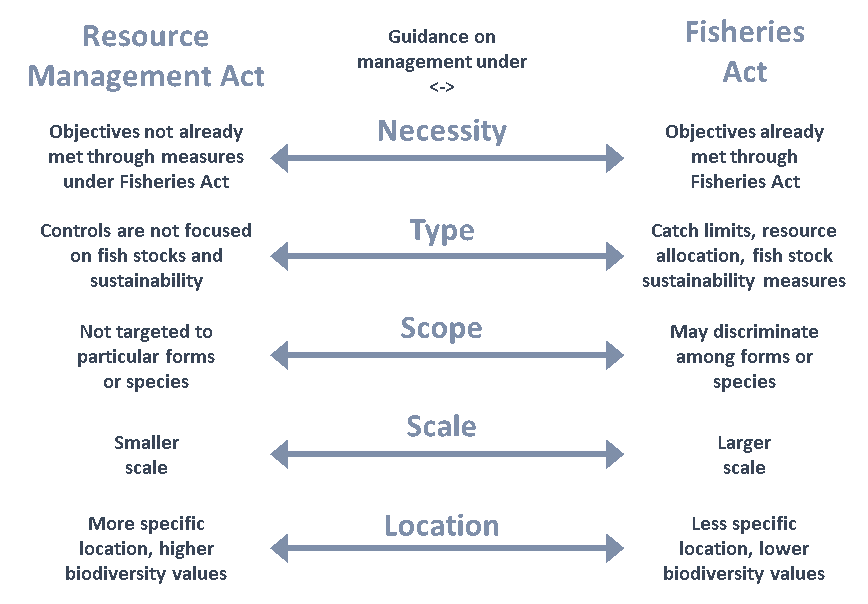

Five indicia identified by the Attorney General for how a council may decide to implement a control that impacts on fisheries management from (Court of Appeal, 2019).

The RMA relates to the use of land, air and water and its purpose is to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources. This includes the responsibility of councils to undertake coastal planning and to maintain biodiversity within the territorial sea (up to 12 nautical miles offshore) through a Regional Coastal Environment Plan.

The Environment Court needed to consider whether regional councils could manage the effects of fishing to maintain biodiversity under the powers of the RMA, without managing the fisheries resources themselves, which are under the remit of the Fisheries Act 1996.[8]

The Environment Court has in this case directed the regional council in the primary role of governance for biodiversity. The Environment Court ruled that Bay of Plenty Regional Council could provide protections, as long the main purpose was in line with those set out under the RMA, having particular regard to the intrinsic values of ecosystems and the relationship of Māori with ancestral waters and taonga.[9]

The Environment Court has in this case directed the regional council in the primary role of governance for biodiversity.

What this decision allows in practice is more complicated, but the Court of Appeal[10] outlined five indicators to provide guidance when considering whether a control could be implemented under the RMA[11] in a way that does not act for fisheries management purposes[12] (see figure above).

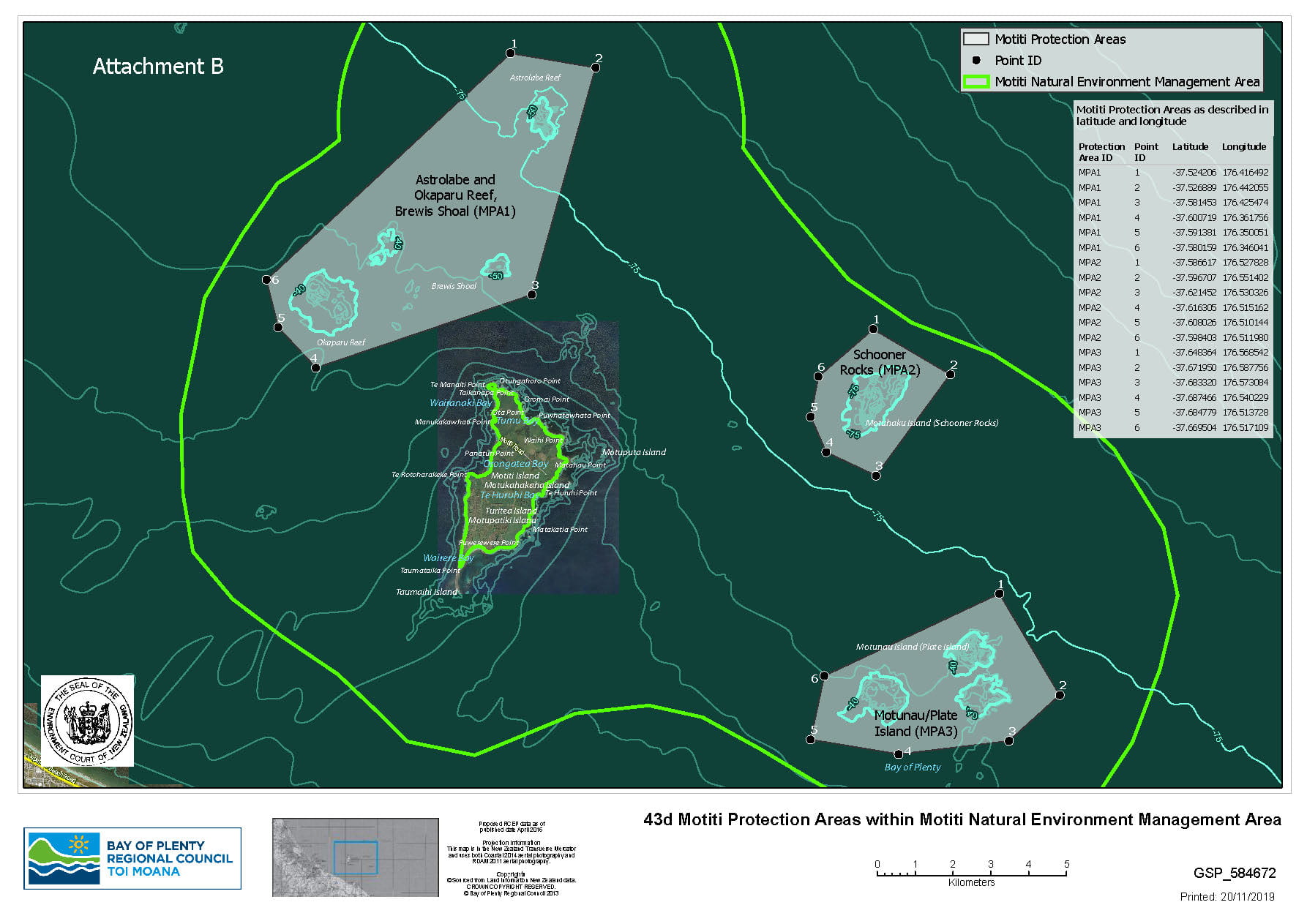

The final decision directs Bay of Plenty Regional Council to implement new rules within its Regional Coastal Environment Plan to protect three reef systems near Motiti and complete scientific monitoring, in collaboration with tangata whenua and multiple agencies, to inform future integrated marine management solutions for the wider Motiti Natural Environment Management Area.[13] The new rules will protect several areas from all fishing (whether commercial, customary, or recreational) (see figure below).

Motiti Protection Areas within Motiti Natural Environment Management Area (Bay of Plenty Regional Council). Click image to enlarge.

The precedence of this decision, which was not universally applauded,[14] means the relationship between the councils, the Ministry of Primary Industries, and the Department of Conservation is entering a new phase. The decision emphasises the importance of co-management that is appropriate to the scale of the issue and provides a way for Fisheries New Zealand, Department of Conservation, regional councils and iwi to work more closely together.[8]

The decision emphasises the importance of co-management that is appropriate to the scale of the issue.

The Court direction to work with tangata whenua and multiple agencies on future marine management solutions presents several opportunities to create a new way of solving problems, using the existing agency tools, applying mātauranga Māori, building capacity of rangatahi in marine science, and exploring contemporary adaptive marine management tools.

In this case, the Regional Council was directed to establish the protection areas and did not itself advocate for the protection. The Council reportedly had some concerns around establishment of the protection areas, as part of an appeal process to the Regional Coastal Environment Plan, as well as having the mechanisms to manage enforcing rules. However, the decision provides greater clarity going forward and the council now has the role of communicating these changes to the wider public. Part of this will be sharing the biodiversity values with communities. The Council will be focusing on working with tangata whenua, the Ministry of Primary Industries, the Department of Conservation and key sector leaders, from the fishing communities, to ensure a collaborative process is established. This is important given that some tangata whenua have stated they do not feel their views were represented in the process or decision.[15]

As the protection areas are governed by rules that sit within a Regional Coastal Environment Plan, they are in place for the life of the plan, which is 10 years. The plan review process will be the mechanism to ensure that the public will have their opportunity to understand the monitoring results of the protection areas and also provide submissions on any future controls in the wider area.

The Motiti decision is an example of hapū using innovative legal means to protect their moana. It may provide councils with a greater certainty in their functions in protecting biodiversity and other resource management issues. Yet it is clear there is ongoing tension in this area. Some argue that the decision actually increases uncertainty and creates confusion in the statutory regime.[16] There is similar confusion potentially created in relation to Māori customary fisheries, and the potential risk of an inconsistent approach between regional councils and therefore uncertainty for local fishers.[17] In contrast, hapū of the Motiti Islands feel the cases reflect issues much wider than those related to fisheries, with how we relate to our environment and the governance of our community to interact in a culturally and environmentally safe manner, and that the Fisheries Act 1996 is not functioning appropriately if it is not considering and responding to the regional context provided in informed regional coastal plans.

The Motiti decision is an example of hapū using innovative legal means to protect their moana. It may provide councils with a greater certainty in their functions in protecting biodiversity and other resource management issues. Yet it is clear there is ongoing tension in this area.

There are several issues that councils may face that require consideration to ensure protections put in place are effective. For example:

- Enforcement. Councils may lack the capacity to effectively enforce protection areas. This means that many protections area would require strong community support and would rely heavily on self-policing.

- Data requirements. Effectively designing and monitoring protection areas relies on having ready access to data at an appropriate level of granularity to be able to make informed decisions. Councils may have access to detailed biodiversity data, at least where appropriate surveying has been carried out. This may or may not be representative of the coastal areas of interest. Fisheries electronic monitoring information is comprehensive, covering all commercial fishing, but may not be readily accessed by councils, particularly in a form that can be easily integrated with other datasets.

- Funding. Many councils may struggle to fund further work in marine protection, particularly where there is not a strong revenue stream (such as from ports) to support this coastal work.

References and footnotes

[1] Schiel, D. R. et al. (2016) Environmental effects of the MV Rena shipwreck: Cross-disciplinary investigations of oil and debris impacts on a coastal ecosystem, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 50(1), pp. 1–9.

[2] Battershill, C. N. et al. (2016) The MV Rena shipwreck: Time-critical scientific response and environmental legacies, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 50(1), pp. 173–182.

[3] RMLA (2018) Motiti Rohe Moana Trust v Bay of Plenty Regional Council, Decision No. [2018] NZEnvC 067.

[4] Umuhuri Matehaere, kaumātua of Te Moutere o Motiti, Chairman for the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust (2017) Statement of evidence of Umuhuri Matehaere on behalf of Motiti Rohe – Moana Trust. Env 2015 AKL 0000134.

[5] Fisheries Act 1996. 186A Temporary closure of fishing area or restriction on fishing methods.

[6] Resource Management Act 1991. 30 Functions of regional councils under this Act.

[7] Fathom (2019) EAFM and the Fisheries Act 1996.

[8] Urlich, S. (2020) The Motiti Decision: Implications for Coastal Management, Resource Management Journal, 1996, pp. 14–19.

[9] Peart, R. et al. (2019) Enabling marine ecosystem-based management: Is Aotearoa New Zealand’s legal framework up to the task?, New Zealand Journal of Environmental Law, p. 31-64.

[10] Court of Appeal (2019) Attorney-General vs the trustees of the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust & Ors. – CA408/2017 [2019] NZCA 532.

[11] Resource Management Act 1991. Section 30(1)(d)(i), (ii) or (vii).

[12] Resource Management Act 1991. Section 30(2) A regional council and the Minister of Conservation must not perform the functions specified in subsection (1)(d)(i), (ii), and (vii) to control the taking, allocation or enhancement of fisheries resources for the purpose of managing fishing or fisheries resources controlled under the Fisheries Act 1996.

[13] Environment Court (2020) Motiti Rohe Moana Trust v Bay of Plenty Regional Council, Decision No. [2020] NZEnvC 050 Court.

[14] Feedback from various stakeholders.

[15] Input from TA Sayers, who whakapapas to the Motiti Islands: An additional concern is that the purpose of this collaboration seems related only to fisheries and not to the cultural, natural, and RMA landscape.

[16] Input from Industry.

[17] Input from Te Ohu Kaimoana: Te Ohu Kaimoana state the Court of Appeal did not deal with any implications on Māori customary (either commercial or non-commercial) fishing interests. Specifically, it did not make a determination on whether a regional council could prevent customary fishing (commercial or non-commercial) for an RMA purpose.