So, what should I do with food scraps at home?

There are many ways to manage your own food scraps.

A 2021 survey published by the Ministry for the Environment suggests that over half of New Zealanders manage at least some of their scraps at home by worm farming, composting, or using a bokashi bin. Moreover, the majority of surveyed New Zealanders who manage food scraps at home think it is easy and worthwhile, and nourish the plants in their gardens using what they produce.

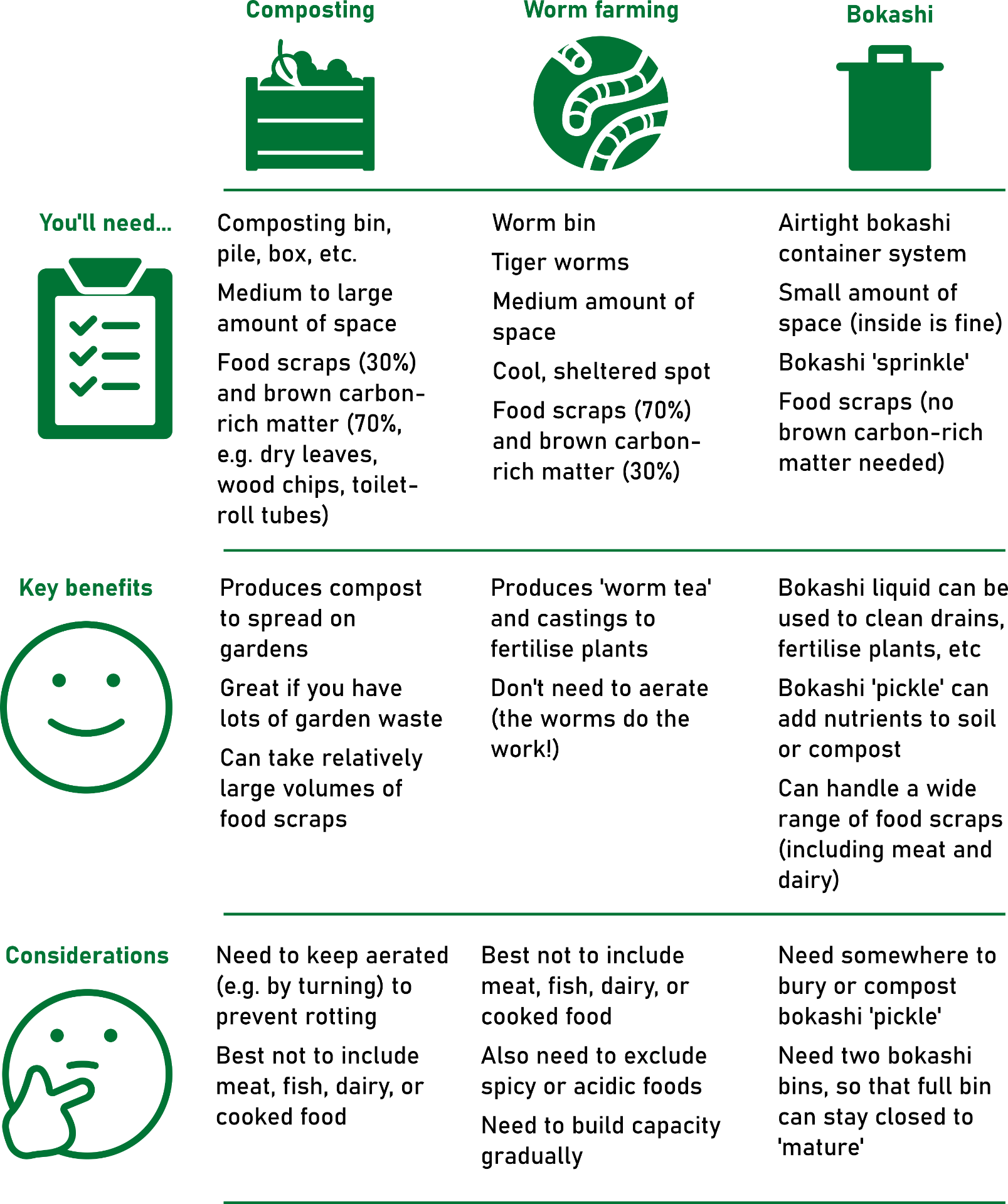

Home solutions at a glance:

To reduce the costs of setting up a composting system at home, subsidies are available in parts of the country (e.g. Auckland, Nelson). Not knowing how to get started can also serve as a barrier, but the Compost Collective has produced helpful resources in multiple languages to empower people to manage their food scraps effectively at home.

The main options for food scraps processing at home are discussed below. Meanwhile, community composting and linking up with neighbours (e.g. via ShareWaste) who have spare food waste processing capacity are good options where space is a limitation – these are discussed in the community section.

Composting at home

A good option if you have plenty of space, a garden that needs nourishing, and a source of brown matter like leaves and twigs.

- Requires outdoor space, including a garden to spread your mature compost on.

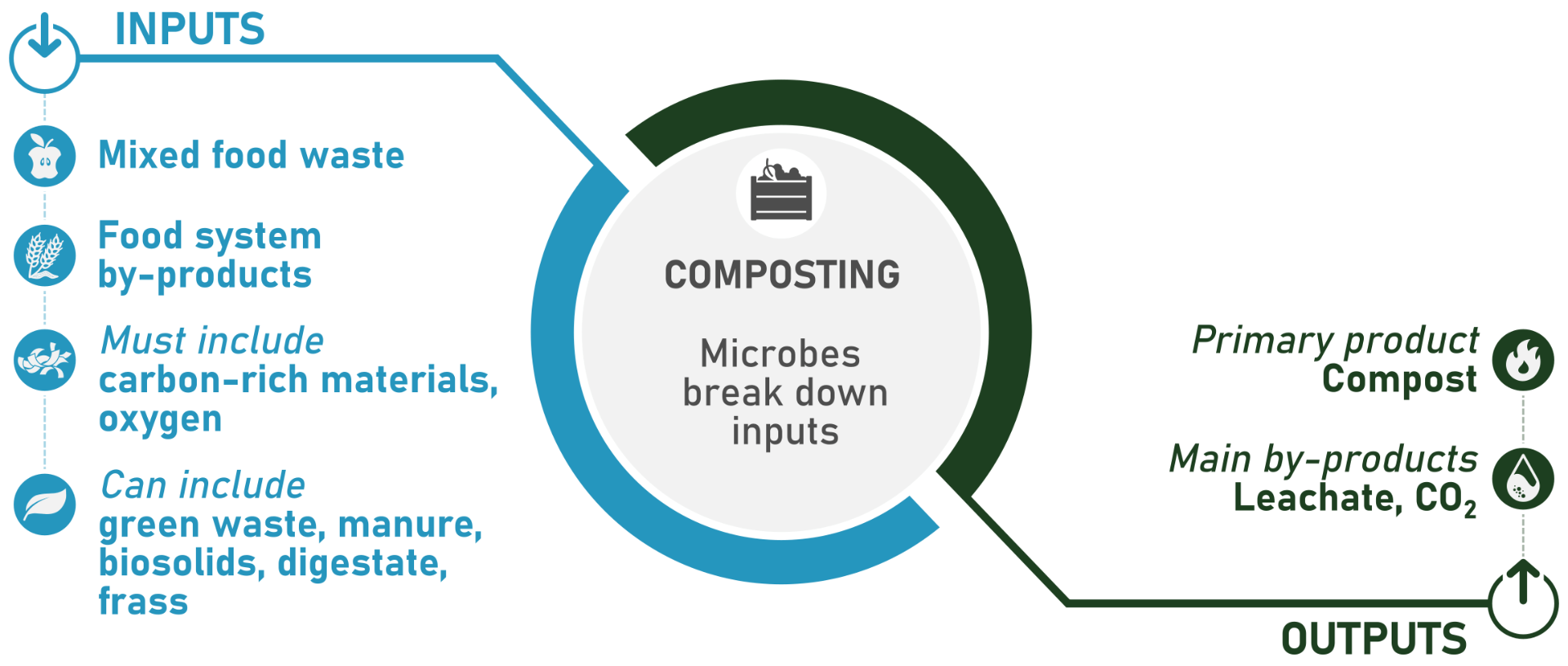

- Requires food scraps (about 30% of inputs) and brown carbon-rich matter (about 70% of inputs, e.g. leaves, twigs, untreated wood shavings, paper, spray-free dried grass clippings).

- Must be turned to keep the pile oxygenated, reducing the risk of rotting food emitting methane and other greenhouse gases, some of which are odorous. While well-managed compost doesn’t produce much methane, carbon dioxide (CO2) (which has a much lower warming potential than methane) is still produced, so composting isn’t emission-free.

- Can be done using enclosed bins, open piles, or composting bays.

- Can take a wide variety of food scraps, but it is generally best to avoid meat, fish, and cooked food to prevent odour and pests (although large-scale, centralised composters often take these materials).

- Can’t readily break down commercially compostable packaging and might struggle with home-compostable packaging.

Composting: inputs, process, outputs

Infographic showing the main inputs and outputs of composting, a food waste processing option that can be applied in the home, community, or by large-scale, centralised enterprises. Food waste and by-products need to be combined with carbon-rich materials to get the ratio of nitrogen and carbon right, and compost piles need to be kept aerated (e.g. by turning) to keep methane production as low as possible. The resulting compost contains nutrients that can be added back to soils. The process also generates CO2 and can produce leachate, although the latter can be minimised through good management practices.

For practical tips to help you get started, check out the Compost Collective’s compost factsheet and Love Food Hate Waste’s composting webpage, as well as the Compost Collective’s video, linked below. Predator Free NZ has also produced some helpful instructions to make sure your compost is rat-proof.

For more information about composting, check out our case studies on Kaicycle and Living Earth, and our content on large-scale, centralised composting.

Watch the Compost Collective’s home composting video to help you get started.

Worm farming at home

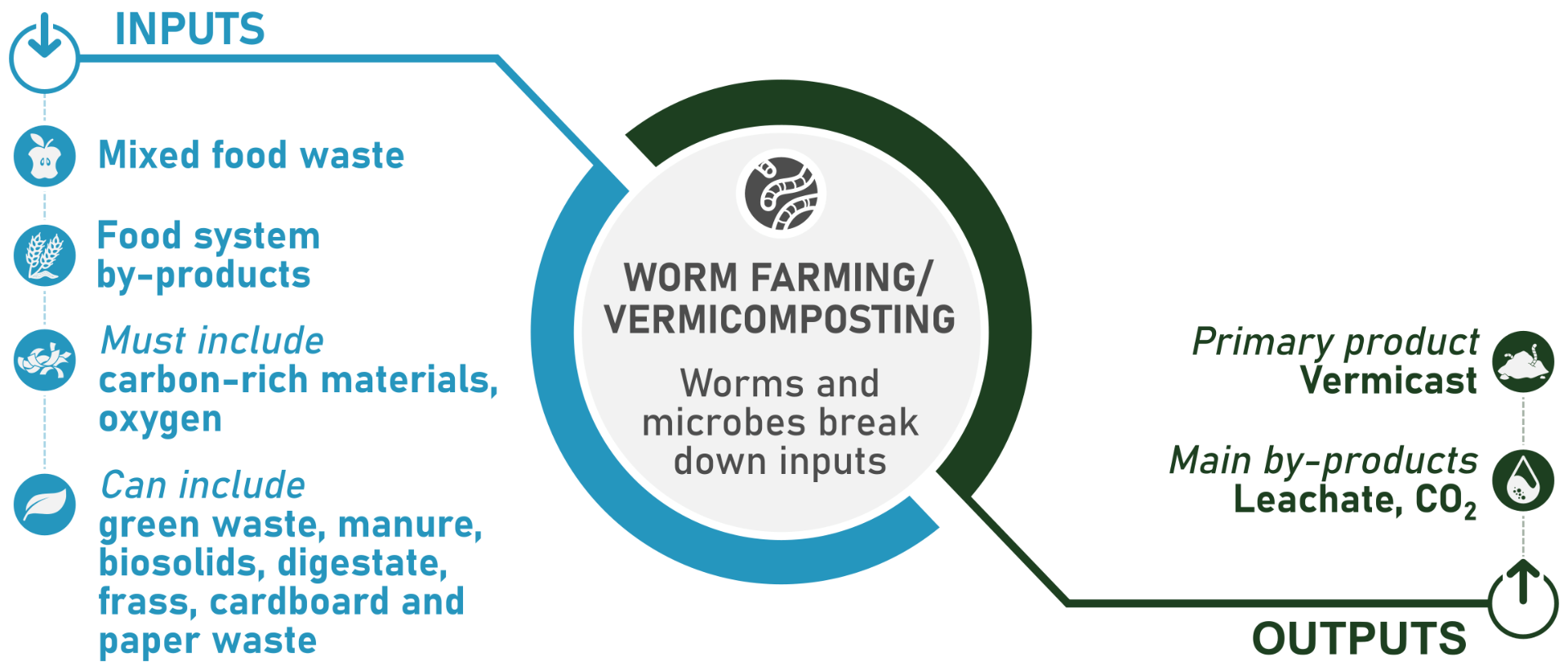

Technically known as vermicomposting, worm farming works well in smaller gardens or on balconies and requires less brown carbon-rich matter (e.g. leaves, twigs) and labour than composting – the worms do the work!

- Takes up less space than composting, requires less brown matter, and requires less space to spread outputs on. This makes worm farming suitable for smaller gardens or even balconies with container gardens.

- Requires food scraps (about 70% of inputs) and a small amount of brown carbon-rich matter (about 30% of inputs). The material should be shredded or cut into small pieces to help the worms process it.

- Doesn’t need turning – the worms aerate the food waste as they eat their way through it, stopping the worm bin from becoming anaerobic and emitting methane – CO2 is the main greenhouse gas emitted.

- Produces worm castings which can be spread around plants or made into ‘worm tea,’ a liquid fertiliser. Nitrogen-rich liquid is also produced by worm farms, and can be diluted and used to fertilise plants.

- Worms can process a wide variety of food scraps, but don’t like spicy (e.g. onions, chillies) or acidic (e.g. citrus) scraps and, as with composting, shouldn’t be given cooked food, or meat or fish.

Vermicomposting: inputs, process, outputs

Infographic showing the main inputs and outputs of worm farming, a food waste processing option that can be applied in the home, community, or by large-scale, centralised enterprises. Fibrous material needs to be added to food waste inputs, and oxygen is crucial too, although the worms themselves incorporate it to the process so no active aeration is needed. The main product is vermicast, which can be used as a fertiliser. The process also generates CO2 and can produce leachate, although the latter can be minimised through good management practices.

For practical tips to help you get started, check out the Compost Collective’s worm farming factsheet and Love Food Hate Waste’s worm farming webpage, as well as the videos from the Compost Collective and Para Kore, linked below.

For more information about worm farming, check out our case study on MyNoke, and our content on large-scale worm farming, or vermicomposting.

Watch the Compost Collective’s video on worm farming at home to help you get started.

If you’re a budding worm farmer and want to understand how to make your set up run as smoothly as possible, check out Para Kore’s longer video on worm farm trouble shooting.

Bokashi at home

If you’re short on space, bokashi could be the solution for you – but you’ll still need occasional access to a bit of garden space. Bokashi can also be used in conjunction with composting or worm farming and can process food scraps that these other methods can’t handle.

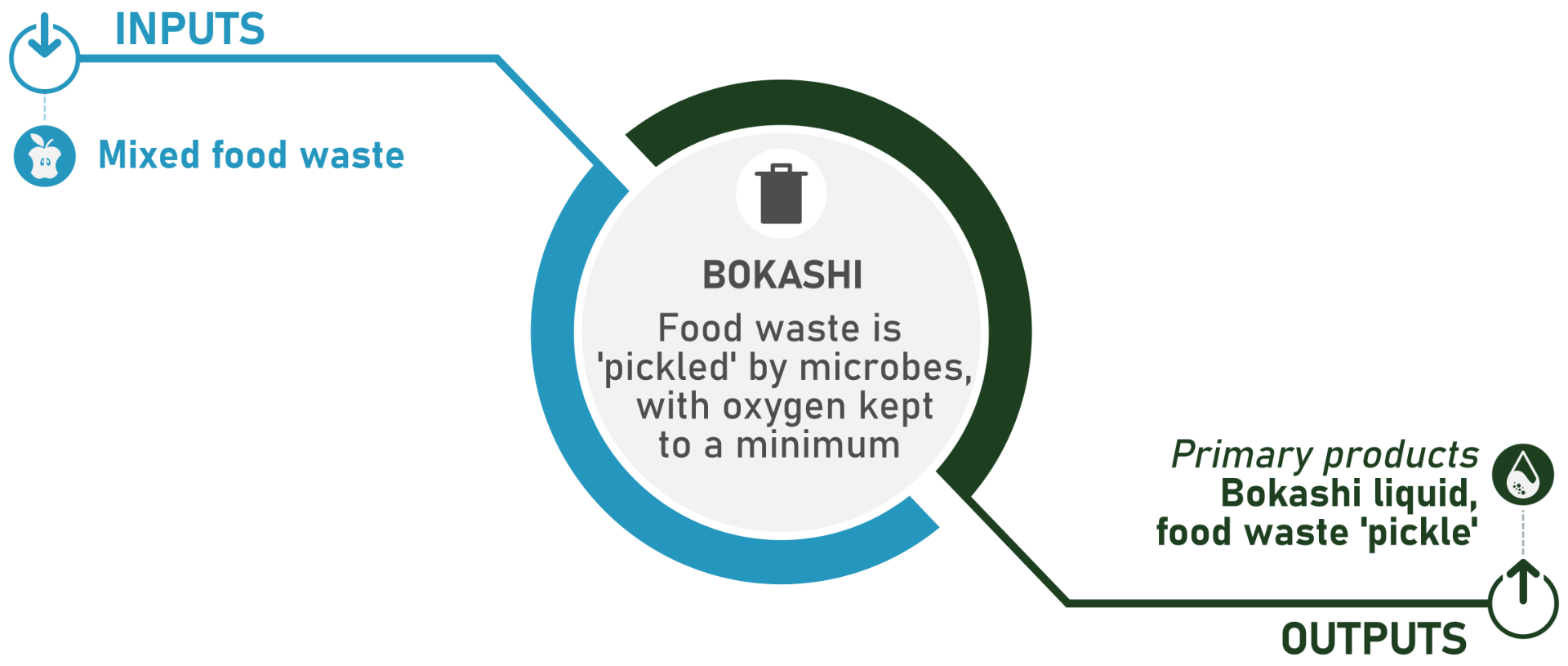

- Bokashi is a type of fermentation. Microbes (commonly called bokashi ‘sprinkle’) such as Lactobacilli (also found in yoghourt) are used to ‘pickle’ food scraps in a near-airtight container, producing a liquid which can be used to clean drains in the home, condition septic tanks, or diluted to fertilise plants.

- The food scraps themselves don’t reduce substantially in volume. Once the bokashi container is full and has had a few weeks of further fermentation, the pickled food scraps need to be dug into a garden or added to a compost bin, where they then decompose. If you don’t have space of your own, you could take your pickled food scraps to a community garden or connect with a neighbour.

- Suitable for a wide range of scraps, including food which you normally wouldn’t compost directly or put in a worm bin, such as meat, fish, and cooked food. The pickling process reduces bad odours.

- While claims that bokashi fermentation produces less greenhouse gas emissions than composting are common, these aren’t well substantiated across the whole bokashi lifecycle (including both the fermentation stage and what happens once the pickled food is added to soil or compost). More research is needed.

Bokashi: inputs, process, outputs

Infographic showing the main inputs and outputs of bokashi, a food waste management solution that can be used in the home. Along with mixed food scraps (which, for bokashi, can include meat, fish, and dairy), it is crucial to ensure that oxygen is kept to a minimum by opening the bin as little as possible. Note that the food waste doesn’t significantly reduce in mass, so the food waste ‘pickle’ that results from the process remains as a by-product which must be either buried in the soil or composted. The bokashi liquid is an acidic leachate that contains carbon, nitrogen, organic acids, and other compounds. When diluted, it can be used as a fertiliser, among other applications.

For practical tips to help you get started, check out the Compost Collective’s bokashi factsheet and Love Food Hate Waste’s bokashi webpage, as well as the Compost Collective’s video (below).

Watch the Compost Collective’s bokashi video to help you get started.

Feeding scraps to animals

Food scraps can also be fed to a wide variety of animals – cats, dogs, chickens, pigs, etc.

As with using food scraps as animal feed at a larger scale, it is important to consider disease transmission risks and animal nutrition and wellbeing. For example, to manage disease transmission risks, pigs should never be fed meat or offal products or food waste that has been in contact with meat or offal products, unless it has been properly treated. Ruminants (e.g. sheep and cattle) should never be fed ruminant protein.

You can find more details about what foods you can safely feed to your pets on the Love Food Hate Waste website, and learn more about the Ministry for Primary Industry’s animal feed rules on their website.

Date released: 29 March 2023

Last updated: 29 March 2023