I put my food scraps in the general rubbish: why is that a problem?

New Zealanders toss 300,000 tonnes of food waste in the rubbish each year, which heads to our landfills.

In addition to the environmental, social, and economic impacts of letting food go to waste, sending food waste to landfill means we can’t utilise it to its full potential. For example, those mouldy carrots from the back of the fridge aren’t so appealing to eat anymore, but they still contain valuable nutrients – they’re still a useful resource, even if no longer edible. If the carrots go in the general rubbish bin, it’s much harder to capture these nutrients and return them to the soil they came from. In a landfill, this potential is wasted, the carrots would simply rot, sending methane – a potent greenhouse gas – into the atmosphere.

To stop food waste from being sent to landfills, part of the government’s new waste strategy calls for councils to provide food scraps collection services for households, businesses to reduce their waste, and individuals to compost their food scraps at home or use collection services.

Landfills release greenhouse gases, but what if you capture the gas?

Sending food waste to a landfill without gas capture is among the most emissions-intensive things you could do with your food waste.

When food waste is landfilled it breaks down without oxygen, releasing methane and other greenhouse gases. Without gas capture systems in place, the equivalent of 1.9 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) are released for every tonne of food waste.

Thankfully, less than 10% of levied waste in Aotearoa goes to landfills without gas capture – most of our landfills capture greenhouse gases and convert it to CO2 which is a less potent greenhouse gas than methane. Some do this as they use it to generate heat and electricity, others by flaring it. By 2026, all municipal landfills are slated to be required to have gas capture systems in place.

However, even at landfills with gas capture systems, some greenhouse gas escapes. This is in part because gas capture systems may only be installed a few years after waste has been deposited, during which time CO2 (initially, while oxygen is present) and methane (later, when oxygen can no longer reach the waste) are released. For landfills with gas capture, an estimated 0.6 tonnes of CO2e are released per tonne of food waste landfilled, but this varies between landfills. Modern, engineered landfills are much better at capturing landfill gas than open older-style landfills (e.g. Redvale Landfill and Energy Park in Auckland captures and uses more than 90% of the methane created, while Wellington’s Southern Landfill captures just 55%).

Greenhouse gas emissions are not the only consideration: landfilling food waste also means its nutrient value is lost, with resources becoming inaccessible as they are buried in the ground.

Could we incinerate mixed waste?

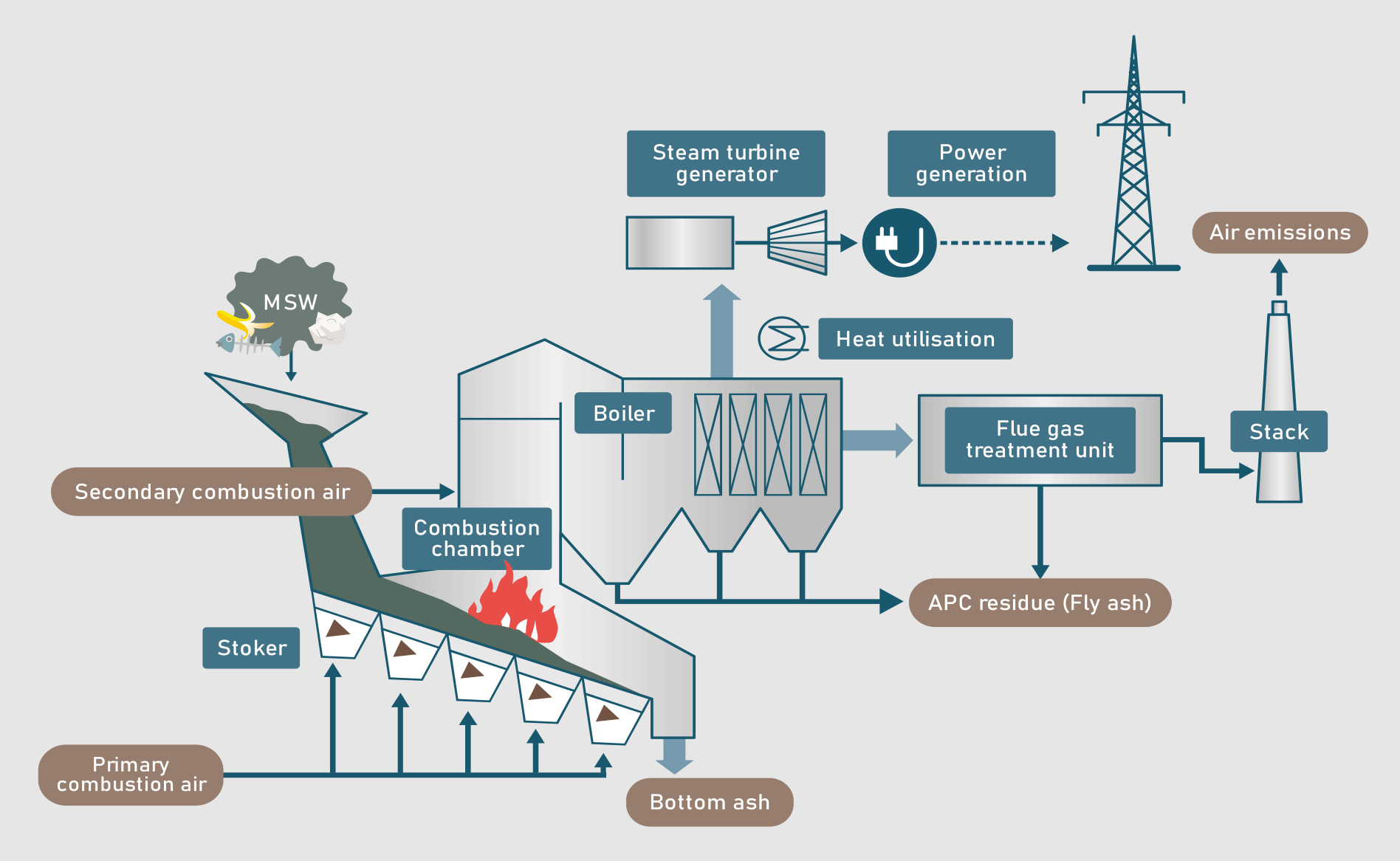

Incineration, where waste is burnt in the presence of oxygen, is an end-of-life waste management solution.

It reduces the mass of waste and produces heat energy that can be used to generate power but otherwise doesn’t yield any useful products. Different types of waste produce different amounts of heat when incinerated, with the incineration of food waste consuming more energy than it produces because of its high moisture content. This means that, for food waste, incineration isn’t a form of energy recovery – it’s a form of disposal.

As with landfilling, the nutrients in food waste are lost when it is incinerated. They are reduced to ash which has very limited usefulness. Incineration also produces fly ash and flue gas, which must be cleaned before discharge, and the residues from cleaning must be dealt with, generally as hazardous waste. In Aotearoa, there is no organised incineration of municipal waste. It is used on a small scale, mostly for hazardous waste, clinical waste, farm waste, and sewage sludge, and its use has declined over time.

Diagram showing an example of the incineration process. In this example, municipal solid waste is used as a feedstock. The fly ash and bottom ash, which get landfilled, contain hazardous and environmentally persistent compounds like dioxins and PFAS. When food waste is incinerated, the amount of energy generated is less than it takes to run the incinerator. Image credit: United Nations Environment Programme.

What if we collect food waste mixed with general waste and separate it later?

A mechanical separator in Chicago separates waste streams for recycling. (Credit: Chris Bentley, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Machines can be used to sort organic waste from general waste, so instead of requiring households and businesses to separate their food waste from other wastes, could we use these machines to do the job instead?

Mechanical separation is an imperfect process: the separated organic stream can still contain at least 5% inorganic material at the end of the process, and it is highly likely that not all organic material is recovered from the organic stream. Contamination extends beyond physical items like plastics: mixed waste can introduce unwanted chemicals into food waste too. This means that the quality of any products (e.g. compost) made from the separate organic stream will be compromised by contamination, limiting its acceptable applications or resulting in its rejection, requiring it to be landfilled after production.

Date released: 29 March 2023

Last updated: 29 March 2023